Friday, April 13, 2007

My mum's farm

On of the reasons Martin and I moved to Canberra was that my mum lives on the outskirts, on a farm with her husband, Greg. They breed Galloway cattle. It's a lifestyle choice.

The farm house is ranch style, profusely carpeted with large cow skins, and the main wall in the living room is completely covered in hundreds and hundreds of trophy ribbons from cattle shows. (Cows are judged both "on the hoof" and "on the hook" - for carcass meat quality.)

I used to be vegetarian, but now I eat meat occasionally - my particular body type just needs it and I start to feel a bit faded if I haven't had meat for a few weeks. I try to stick to organic, kindly-raised animals (like my mum's cows) but I'm still squeamish and guilty about the idea of eating dead things. And in the yoga community, obviously there are a lot of vegetarians who feel very strongly about it. (I met one girl at a Krishna Das workshop. I mentioned that I was going to stay at my mum's cattle farm and she just gazed at me with her big melting eyes, leaned forward and put her hand on my shoulder, and said "I'm sorry, that must be so hard for you...")

So, there are a lot of confronting things for me about staying at the farm. The cows all have names, and Mum talks to them and feeds them every day and fusses over the adorable calves. A few of the baby boys are saved as bulls, but most are castrated to become steers, and then their names get changed into numbers because their days are numbered. Every month two of the steers get taken to the slaughterhouse where they are killed by a bolt gun through the forehead. Greg always sends two at a time "so that they have a mate" - that way they get less stressed while they are waiting at the slaughterhouse overnight.

A lot of people are disturbed thinking about how their steak used to have a name. Yet is it ethically better to buy a plastic-wrapped hamburger at the supermarket? You don't change the reality of where that meat came from by avoiding thinking about it; that just seems like moral cowardice. It certainly doesn't disturb my mum and Greg; they spend the day affectionately working with the cows and then enthusiastically tuck into large slabs of meat for both lunch and dinner.

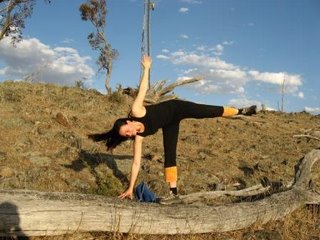

I'm not sure how many acres the farm is, but you can walk around the farm in about two hours. There are hills (Big and Small), a creek, several watering holes, and a small, patchy eucalypt forest. The cows usually climb to the top of Big Hill in the evenin

gs, perhaps for the grazing or perhaps for the sunsets and sunrises. Which are spectacular.

gs, perhaps for the grazing or perhaps for the sunsets and sunrises. Which are spectacular.When Martin and I first moved to Australia we spent a few months living on the farm. The big sky, endless views, and menagerie of animals were quite a shock after our urban lifestyles in DC. Every day we walked around for hours, trying to sneak up on the kangaroos at the watering holes, poking sticks at echidnas in the forest, or feeding carrots to the neurotic ex-racehorse in the Small Hill paddock. (I used to bring a curry-comb and brush the horse, but every time I did, he'd get a gigantic boner and it was just too disturbing.)

The bands of kangaroos hopping about tick off Mum and Greg, because four kangaroos eat as much grass as one cow, and grass is a scarce commodity in the dry climate. Every once in a while, they hire a kangaroo hunter who comes with a shotgun and leaves them lying where they fall.

By law you're not allowed to use the bodies for meat unless you have a permit - which seems disrespectful as well as wasteful to me; you're stealing their lives without even putting those lives to use. But Mum's dog, Fenris, certainly enjoys finding those rotting kangaroo carcasses; he rolls around in them ecstatically and carries their bones proudly back to the front door.

By law you're not allowed to use the bodies for meat unless you have a permit - which seems disrespectful as well as wasteful to me; you're stealing their lives without even putting those lives to use. But Mum's dog, Fenris, certainly enjoys finding those rotting kangaroo carcasses; he rolls around in them ecstatically and carries their bones proudly back to the front door.Reading back on what I've written, death is a big theme of life on the farm. I haven't even mentioned the cat, Ash, who is a deadly hunter and likes to leave disembowelled possums lying in front of the bathroom door, which really wakes you up in a hurry when you go to the toilet in the morning, let me assure you. Nor have I mentioned the cow skeletons lying around everywhere on the farm, strewn amongst the rocks in various stages of sun-bleach. (When I was in Australia two years ago I thought the cow skulls would make great accessories for modern art projects. It was a terrible, terrible idea but that's a story for another day.)

There's a classic Buddhist meditation where you imagine your own body aging, and then you visualize your own corpse rotting away into a skeleton. Part of the idea of this is to reinforce just how mortal and fleeting our lives are - and to remind us how much we should treasure every single living breath. It's an idea most people who've suffered near-death experiences are familiar with.

Thinking about death doesn't make life grim - at least not for me. It's when I get complacent and ungrateful, when I start subconsciously assuming things are going to stay this way forever, that the joy starts to sneak away...

So maybe that's why I have so many vivid memories of my time living on the farm.

It's a harsh, dry, unforgiving, spectacularly beautiful landscape.

It